Welcome back!

In my previous post I had discussed about pain and central sensitization and in this post, I will be focusing on the physiotherapist’s role in treating patients with central sensitization pain.

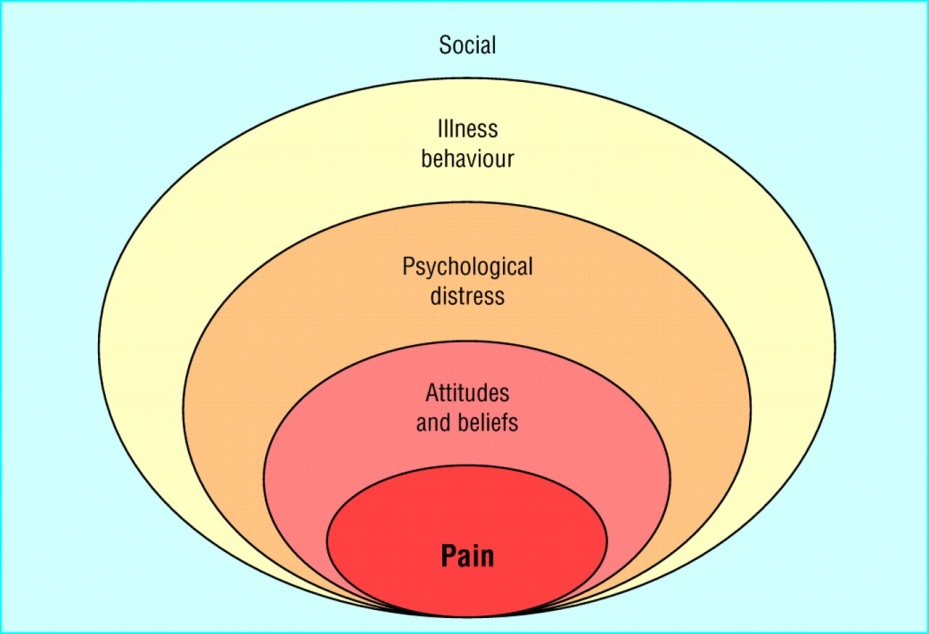

Figure 1 adapted from http://www.dreamstime.com

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is often associated with psychological distress and maladaptive belief’s. Kinesiophobia is the fear of movement and this fear changes how we move.

The fear avoidance model describes how the belief that pain is a sign of damage leads to pain-related fear and avoidance.

The experience of pain as unpredictable, uncontrollable and intense makes the movement of the patient threatening. The past personal experiences of pain, societal beliefs, failed treatments and diagnostic uncertainty or diagnosis of an underlying pathology that could not be fixed often makes the condition of the patient worse and lands them into physical inactivity.(1)

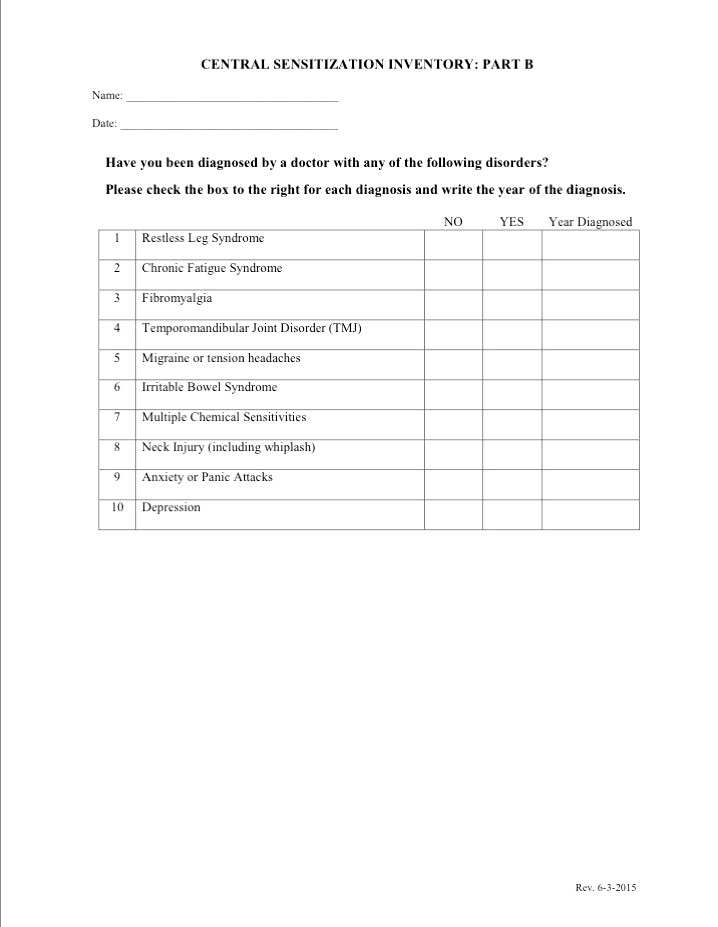

Figure 2 adapted from http://www.doctorsofpt.com

According to WHO:

“Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure”. (2)

According to physical activities statistics 2015, British Heart Foundation, 13% of UK adults are sedentary for longer than 8.5 hours a day.

The UK analysis of the global burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors study found physical inactivity and low physical activity to be the fourth most important risk factor in the UK.

They estimated that physical inactivity contributes to all most 1 in 10 premature deaths from coronary heart diseases and 1 in 6 deaths from any other cause. As well as health burden in the UK, physical inactivity has a significant financial burden with the direct financial cost of physical inactivity to the NHS greater than £900 million in 2009/10.

In the UK 44% of adults never do any moderate physical activity.(2)

Age group of adults aged 25 and older more than half of sedentary time was spent in watching television.(2)

Figure 3 adapted from whyexercise.com

DELETERIOUS EFFECTS OF INACTIVITY

The sedentary lifestyle is deleterious to musculoskeletal health and is a risk factor for non communicable diseases including cardio-metabolic syndrome.

The joint surfaces degenerate due to reduced synovial fluid production that protects joint surfaces. This risk factor also persists in individuals who exercise routinely but have patterns of prolonged periods of inactivity during the day.(4)

The energy expenditure in sedentary lifestyle is very low. Research suggests that sedentary behaviour is associated with poor health at all ages.

Inactivity is associated with the prevalence of back complaints and many of the risk factors of back pain being those of cardiovascular disease.

A sedentary life style along with smoking and unhealthy weight contributes to premature ageing. The mechanism is associated with shortening of telomere length. Telomere length is further compromised with oxidative stress and inflammation associated with unhealthy lifestyles leading to non communicable diseases.(5)

(A telomere is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences at each end of a chromatid, which protects the end of the chromosome from deterioration of from fusion with neighbouring chromosomes).

The researchers have focussed on volume of physical activity and quantified sedentary activity. Tudor-Locke and colleagues recently quantified daily inactivity based on a step-defined sedentary lifestyle index, <5000 steps/day. The use of such a marker is useful in the musculoskeletal assessment of people with disabilities such as back pain and serves as an evaluation tool.(6)

BENEFICIAL EFFECTS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Regular physical activity is associated with positive health status and is beneficial for the multi system functioning including musculoskeletal health.

People who are physically active are at lower risk of cardiovascular disease.

To produce the maximum benefit, exercise needs to be regular and aerobic. This should involve the use of the major large muscle groups steadily and rhythmically.

Physical activity done throughout the day protects musculoskeletal health and is highly recommended for protection against bone impairment.

Standing offices and treadmill workstations are promoted to break-up periods of prolonged sitting during the work day.(9)

The physical activity guidelines suggest 150 minutes of moderately intense activity per week. The low level of exercise is substantial as it is consistent with positive health, reduced morbidity and improved response to healthcare management, particularly for older people.(7)

Tolerable activity is recommended in clinical practice even for acute back pain as it reduces pain related anxiety and depression.

In chronic low back conditions people work less and are generally less physically active. Mc Donough and co-workers recently reported that chronic low back pain people can increase their working daily over 8 weeks in a pedometer driven walking program.(8)

The program was reported to be safe and was able to reduce pain and disability and improved function.

WHO grading of moderate and vigorous intensity physical activity

Figure 4 adapted from http://www.who.int

Chronic pain is often associated with physical inactivity.

How do you think the holistic patient centred care can be delivered?

Should we as physiotherapist’s undertake the responsibility and behavioural intervention of the patient?

In chronic musculoskeletal pain, even though nociceptive pathology is subsided, the brain of the patients has typically acquired a protective pain memory. Exercise therapy is hampered by such pain memories.(3)

So, we need to alter the pain memories in patients by integrating pain neuroscience education with exercise therapy for targeting the brain circuitry orchestrated by the amygdala (the memory of fear centre in the brain)(3)

Figure 5 adapted from neuroplastix.com

In the initial phase, intensive pain neuroscience education is given followed by exercise therapy for applying the exposure without danger principle.

Considering patients perceptions about exercises, therapists should try to decrease the anticipated danger of the exercises by challenging the nature and reasoning behind their fears, assuring the safety of the exercises and increasing confidence in a successful accomplishment of the exercise.

Chronic condition is often characterized by brain plasticity that leads to hyper excitability of the central nervous system. Desensitizing therapies are used along with exercise therapy.

Cognition targeted exercise therapy using therapeutic neuroscience education is given.

The principles of cognition targeted exercise should focus on time-contingent exercises, goal settings, address perceptions about exercises, motor imagery, address feared movements and make use of stress.(3)

The goal of cognition targeted exercise therapy is system desensitization or graded, repeated exposure to generate a new memory of safety in the brain, replacing or bypassing the old and maladaptive movement- related pain memories.

Hence, such an approach directly targets the brain circuits orchestrated by the amygdala.

Exercise stimulates the brain plasticity by stimulating growth of new connections between cells in a wide array of important cortical areas of the brain.

Recent research from UCLA demonstrated that exercise increased growth factors in the brain and helps brain to grow more new neuronal connections.

According to a study done by the department of exercise science at the University of Georgia, even briefly exercising for 20 minutes facilitates information processing and memory functions.

Exercise affects the brain on multiple fronts. It increases heart rate which pumps more oxygen to the brain and also aids the bodily release of a plethora of hormones, all of which participate in aiding and providing a nourishing environment for the growth of brain cells.(13)

Figure 6 adapted from www.peacefulplaygrounds.com

LATEST EVIDENCES OF EXERCISES IN RELATION TO CHRONIC PAIN

- Fransen M, et al. 2015, conducted a Cochrane systematic review and found that among people with knee osteoarthritis land based therapeutic exercise provides short-term benefit that is sustained for at least 2-6 months after cessation of formal treatment

- Doerfler D, et al.2015 conducted a randomised clinical study to compare the effect of high-velocity quadriceps exercises with that of slow-velocity quadriceps exercises on functional outcomes and quadriceps power following total knee arthroplasty and found that high velocity quadriceps exercises may be an effective rehabilitation strategy in conjunction with a standardised progressive resistance exercise program beginning 4-6 weeks after total knee arthroplasty.

- Brage K, et al. 2015 conducted a preliminary randomised control trial to evaluate the effect of training (neck shoulder exercises, balance and aerobic training) and pain education versus pain education alone on neck pain and found that pain education and specific exercise training reduced neck pain more than pain education alone in patients with chronic neck pain.

WHY IS AN EXERCISE OR FITNESS PROGRAM AN ESSENTIAL PART OF YOUR PAIN CONTROL REGIME?

Because….,

- It improves muscle strength.

- improves mobility of the joint, reduces stiffness thus alleviating pain.

- Stretching exercises provides flexibility to joint contractures and also decrease the chance of muscle bleeds.

- Co-ordination and balance is improved decreasing the chance of further injury to the joint.

- Improves confidence and ability to participate.

- Feeling of well being and decreases anxiety

- It augments the release of endorphins (natural chemical messengers in the body dampening the pain sensitivity)

- Increases endurance and encourages weight loss.(13)

OTHER PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENTS FOR PAIN RELIEF

- Mobilizations or tractions – reduces pain by increasing joint movements

- Massage – induces relaxation and decreases muscle spasms.

- Splinting or supports – helps to decrease pain by resting joint

- Whirlpool, Hydrotherapy, Swimming and acquacize – strengthens muscle and reduces pain by decreasing muscle spasms

- Hot packs/heating pads-relaxes tight muscles causing tissues to relax and vasodilatation.

- Ice packs – decreases pain by reducing the conduction of pain signals

- Shoe inserts or foot orthotics – reduces pressure on the foot and accommodating foot deformities

- Crutches, cane or wheel chair – reduce the stress and pain on ankle, knee or hip.

- Acupuncture – chronic pain and muscle spasm respond well to this type of treatment.

- Taping-helps prevent injury and return back to sports.

- Manipulations-relives pain and releases endorphins.

There are various other electrical modalities which could be used as an adjunctive exercise treatment.

CONCLUSION

I hope that through this blog I have made an attempt to provide a brief insight into understanding of central sensitization pain, recognizing its effects on various bio psychosocial factors, its assessment using various methods and last but the important means of its management through physical exercise therapy and education.

My take after going through the various literatures and articles on central sensitization pain and its management in a nut shell is as follows

- Listen, understand and act accordingly approach works well in managing the patients

- Recognizing the whole effects of pain including various bio psychosocial effects and treat it accordingly

- Never to have a blind faith for one paradigm in managing patients with chronic pain

- Three components of pain should be considered and they are

1) Cognitive behavioural beliefs-pain beliefs

2) Functional behavioural aspect- movement patterns

3) Life style adaptations due to pain and avoidance of

activities.

Focusing on good sleep patterns, eating a healthy diet, avoiding alcohol, maintaining an exercise program, utilizing relaxation techniques are strategies helpful in decreasing sensitivity within the body.

It is important for us as physiotherapists to educate our patients on these principles.

I felt my first blogging experience was challenging initially but through its process i started enjoying it and found a new means of enriching my knowledge through research on current trends in the given topic.

It was a great platform to share the knowledge with other colleagues, getting the feedbacks and valuable comments was an overwhelming experience.

I hope you have enjoyed my blog and found it interesting and informative.

Many thanks for going through my blog and for your likes and comments.

Finally, I would like to conclude saying,

“Keep moving and stay healthy”.

Figure 7 adapted from ethoshealth.com.au

REFERENCES

- Bunzli, S., Smith, A., Schütze, R. and O’Sullivan, P. (2015). Beliefs underlying pain-related fear and how they evolve: a qualitative investigation in people with chronic back pain and high pain-related fear. BMJ Open, 5(10), p.e008847.

- WHO phsyical activity statistics, 2015, British heart foundation

- Nijs, J., Lluch Girbés, E., Lundberg, M., Malfliet, A. and Sterling, M. (2015). Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual Therapy, 20(1), pp.216-220.

- Hootman, J., Macera, C., Ham, S., Helmick, C. and Sniezek, J. (2003). Physical activity levels among the general US adult population and in adults with and without arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 49(1), pp.129-135.

- Cherkas, L. (2008). The Association Between Physical Activity in Leisure Time and Leukocyte Telomere Length. Arch Intern Med, 168(2), p.154.

- Tudor-Locke, C., Craig, C., Thyfault, J. and Spence, J. (2013). A step-defined sedentary lifestyle index: <5000 steps/day. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab., 38(2), pp.100-114.

- Hill, J. (2008). Dietary and Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Obesity Management, 4(6), pp.317-318.

- McDonough, S., Tully, M., Boyd, A., O’Connor, S., Kerr, D., O’Neill, S., Delitto, A., Bradbury, I., Tudor-Locke, C., Baxter, G. and Hurley, D. (2013). Pedometer-driven Walking for Chronic Low Back Pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(11), pp.972-981.

- Wilson, F. (2015). Grieve’s Modern Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy (Fourth edition):. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(20), pp.1352-1352.

- Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL.. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review.. Br J Sports Med 2015;

- Doerfler D, Gurney B, Mermier C, Rauh M, Black L, Andrews R.. High-Velocity Quadriceps Exercises Compared to Slow-Velocity Quadriceps Exercises Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Clinical Study.. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2015;

- Brage K, Ris I, Falla D, Søgaard K, Juul-Kristensen B. Pain education combined with neck- and aerobic training is more effective at relieving chronic neck pain than pain education alone – A preliminary randomized controlled trial.. Man Ther 2015;

- Physiotherapy another approach to pain management by Jenny Aikenhead, physiotherapist, Alberta, children’s Hospital, Calgary, Alberta.

- Figure 1 adapted from http://www.dreamstime.com

- Figure 2 adapted from http://www.doctorsofpt.com

- Figure 3 adapted from whyexercise.com

- Figure 4 adapted from http://www.who.int

- Figure 5 adapted from neuroplastix.com

- Figure 6 adapted from http://www.peacefulplaygrounds.com

- Figure 7 adapted from ethoshealth.com.au